Sublime

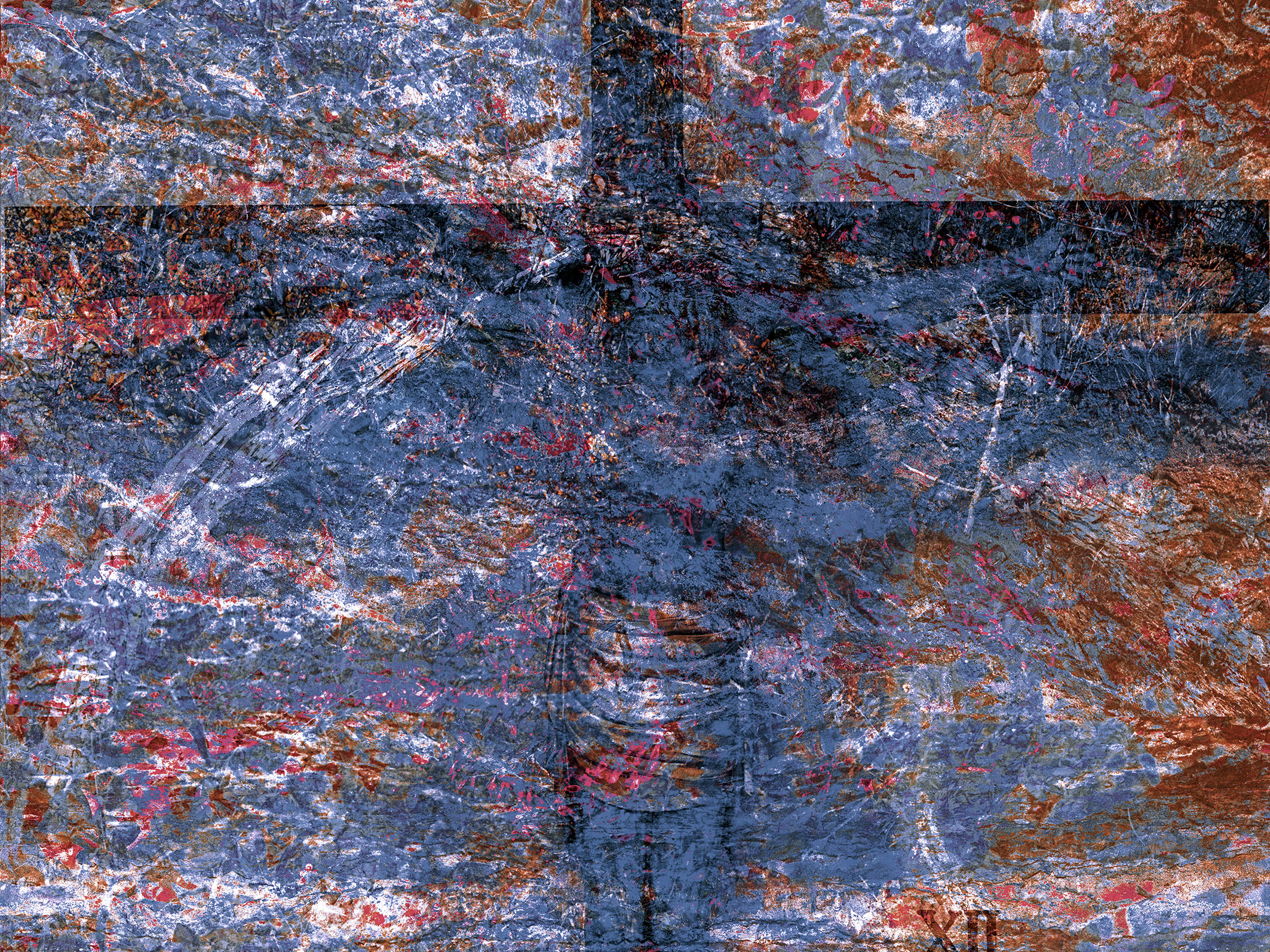

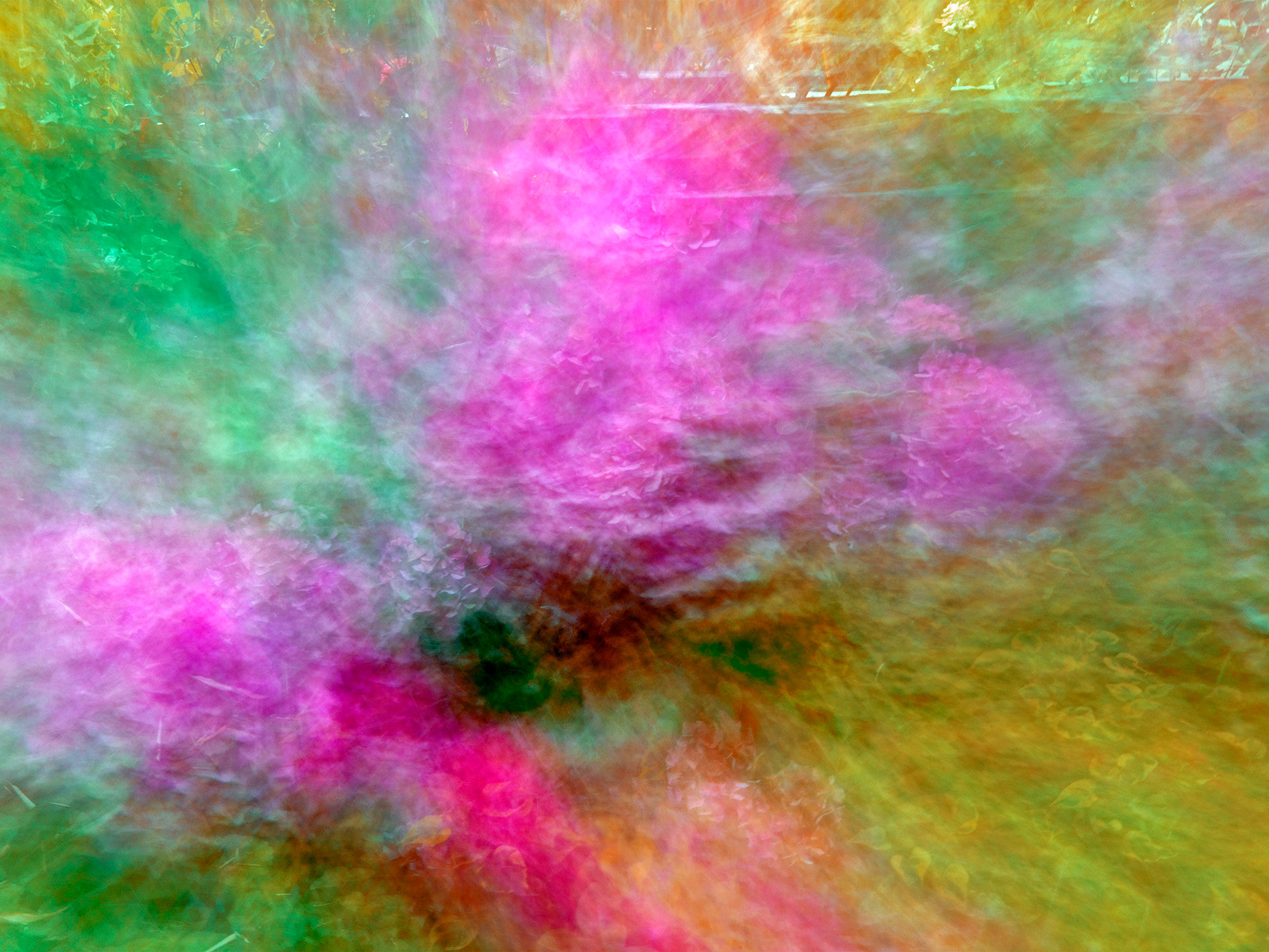

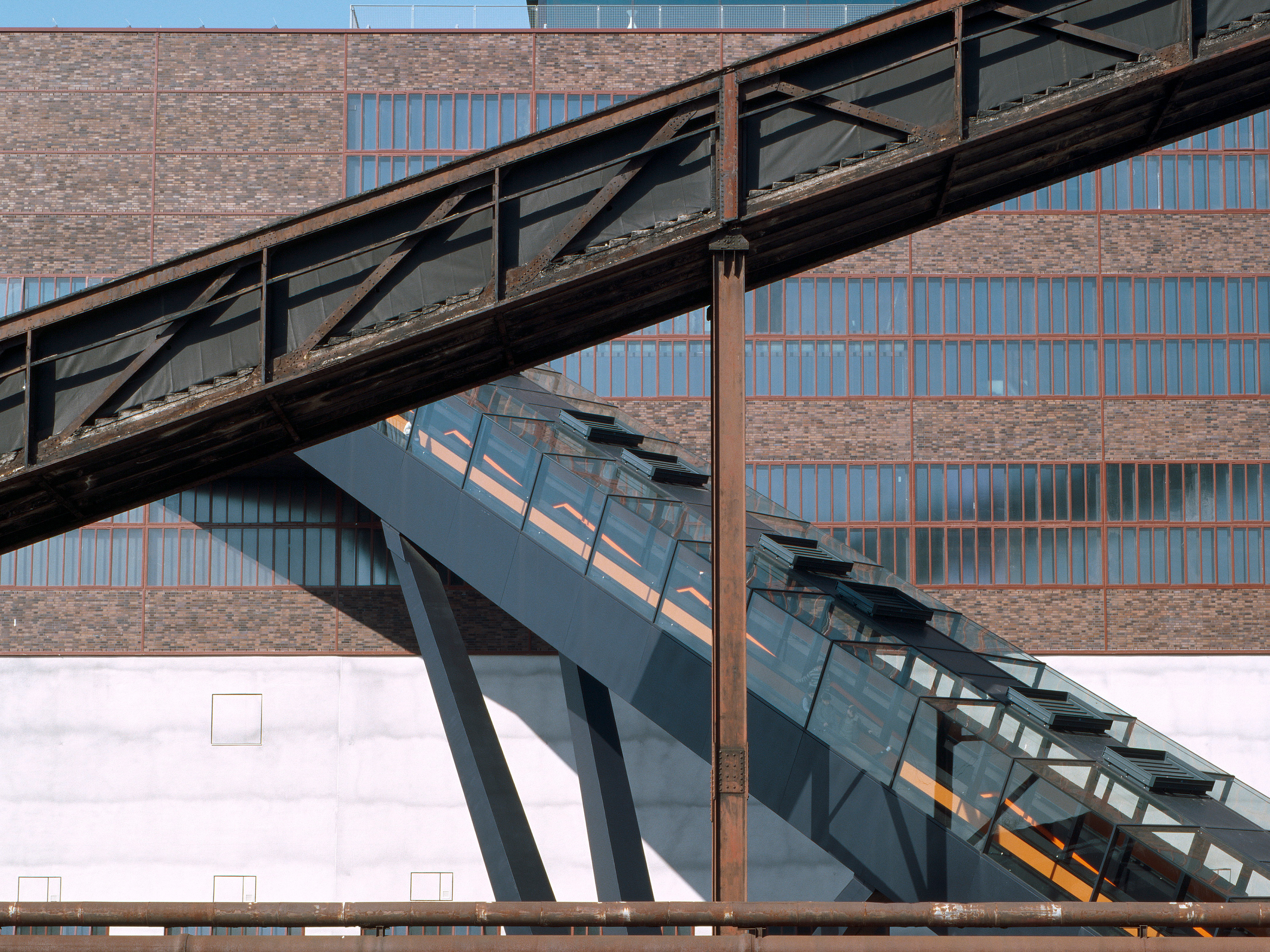

In recent decades, the art-historical discourse on the sublime has been shaped by a persistent tension: the contradiction between the metaphysical, overwhelming, and contemplative dimensions traditionally associated with the sublime—from Longinus and Burke to Kant, Lyotard, and the phenomenologists—and the culturally inscribed function of photography as evidence, documentation, and visual clarity. While the sublime has always demanded an encounter with the limits of human cognition, photography has been anchored, since the nineteenth century, to the visible, the verifiable, and the empirically grounded. In this dichotomy, transcendence and photographic realism were positioned as mutually exclusive. The series Sublim breaks through this historical antagonism by using photographic means not to circumvent the sublime, but to generate it. Central to this is the deliberate use of the large-format camera, whose extreme depth of field and crystalline precision traditionally signify empirical exactitude. Yet instead of undermining or dissolving this precision, Sublim redirects it: hyperreal clarity becomes the catalyst for contemplative perception. The sharply rendered detail—ordinarily a guarantee of sober objectivity—here opens a space of heightened presence and interior intensity. Realism becomes not the obstacle to the sublime but its vehicle. Within these images, familiar industrial and everyday landscapes appear in a state of optical lucidity that lifts them from their functional context. The profane is not beautified, not romanticized; instead, through precision it is carried into a depth where the ordinary reveals its metaphysical resonance. This transfiguration through clarity forms the methodological core of the series: transcendence does not arise by dissolving the visible but by penetrating it. The sublime emerges not—as in Romanticism—through monumental natural spectacle, but through a state of heightened attentiveness that transforms perception into recognition. In this way, Sublim aligns itself with the sensibilities of artists such as James Turrell, Agnes Martin, and Wolfgang Laib, who cultivate states of stillness, presence, and inner transformation. Yet unlike these practices—which often detach perception from descriptive fidelity—Sublim insists on the full visibility of the real. The images refuse abstraction; they hold fast to what exists, and it is precisely this fidelity that opens the threshold to deeper, more contemplative insight. Here, the sublime is not an escape from reality but its intensified revelation. A dialogue emerges as well with contemporary photography exploring metaphysical or existential conditions—Hiroshi Sugimoto’s temporal horizons, Thomas Struth’s institutional spaces, Andreas Gursky’s perceptual expansions. Yet Sublim diverges in a crucial way: it renounces monumental staging, digital manipulation, and visual spectacle. Its effect is generated solely through intrinsically photographic means—sharpness, detail, tonal modulation, spatial depth—and unfolds quietly, yet transformatively. This aesthetic precision gains particular urgency in the digital era. Jean Baudrillard, in Why Hasn’t Everything Already Disappeared?, describes how the contemporary flood of images dissolves reality into a state of simulacral dispersal, in which visibility itself begins to vanish. In a world where every image is technically perfect, perfection becomes meaningless: images become interchangeable, smooth, and soulless. Photography risks losing its identity as a medium of singular artistic insight; it drifts toward insignificance within a culture of visual overproduction. Sublim positions itself at this critical juncture and formulates a photographic new beginning. The series does not merely claim insertion into art history—it articulates, deductively and demonstrably, the reasons such an insertion is necessary. It shows that photography, precisely through its technical foundations, possesses an indispensable role in contemporary aesthetics. The large-format camera—long a symbol of empirical accuracy—becomes the instrument through which a new form of ontological visibility is recovered. Where reality threatens to evaporate in the digital image-stream, Sublim produces a clarity that is not superficial but existential. This radical sharpness renders visible what is seen—and simultaneously reveals what lies beyond direct visibility. What emerges is a new form of evidence: a visibility that does not stop at perception but transitions into understanding, unveiling a spiritual dimension embedded in the structures of the everyday world. Thus the series moves from appearance to revelation. This leads to the logical and deductive conclusion: If the digital image world causes reality to dissolve, then Sublim demonstrates that only a precise, deep-reaching penetration of the real can reopen access to what might be called “actual reality.” The sublime arises at the moment when the world becomes clear enough to disclose its hidden metaphysical dimension. The precision of the large-format camera becomes evidence that lucidity does not dispel mystery but is its precondition. Thus the series advances not just an aesthetic position but a historical claim: Sublim shows that photography in the twenty-first century can articulate a renewed form of the sublime—one anchored in the world yet opening into a realm of contemplative and spiritual intensification. In this sense, Sublim is not merely an addition to the lineage of the sublime; it is a necessary new beginning for photography itself.