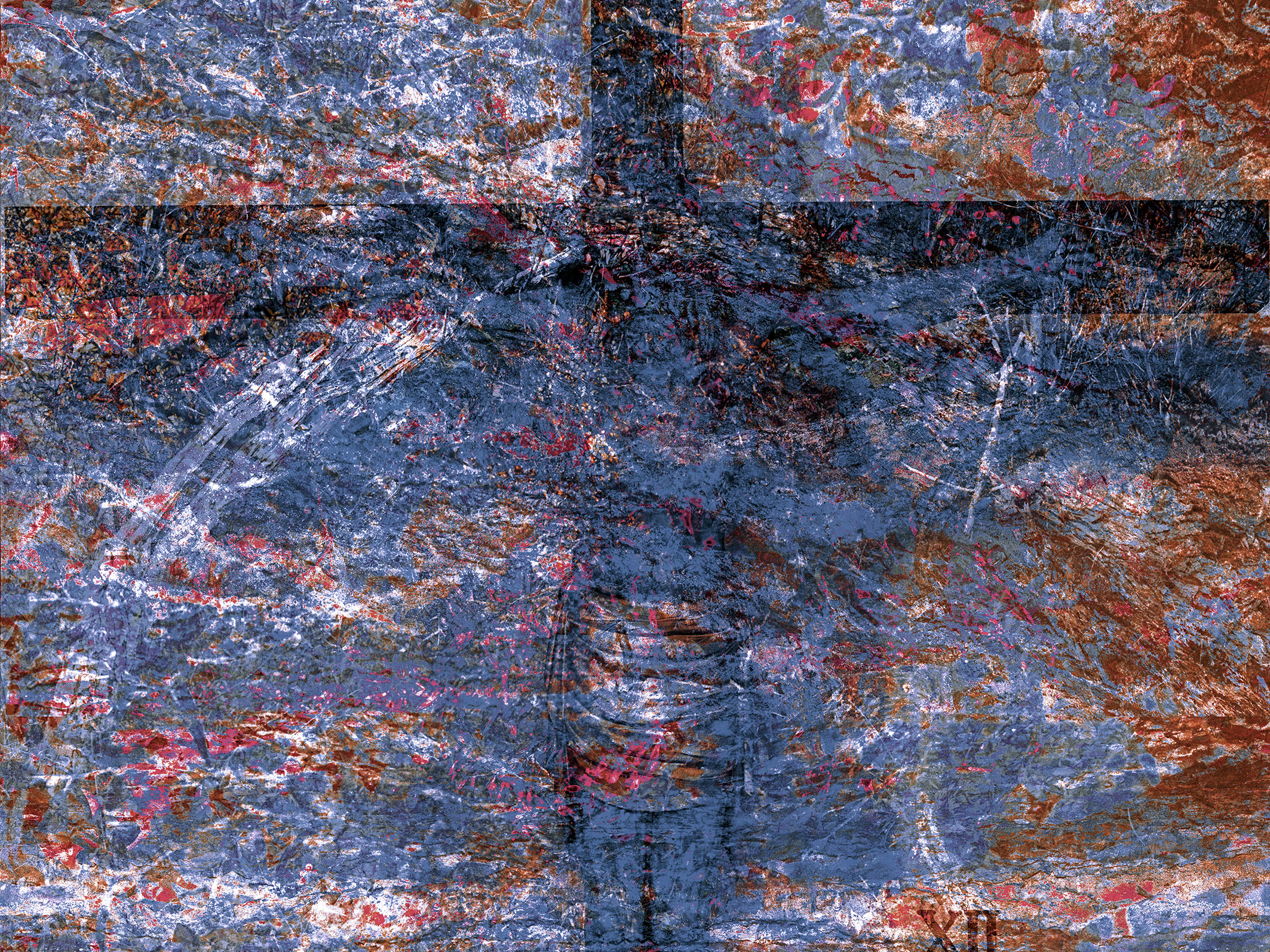

Garden impressions/Homage to Monet

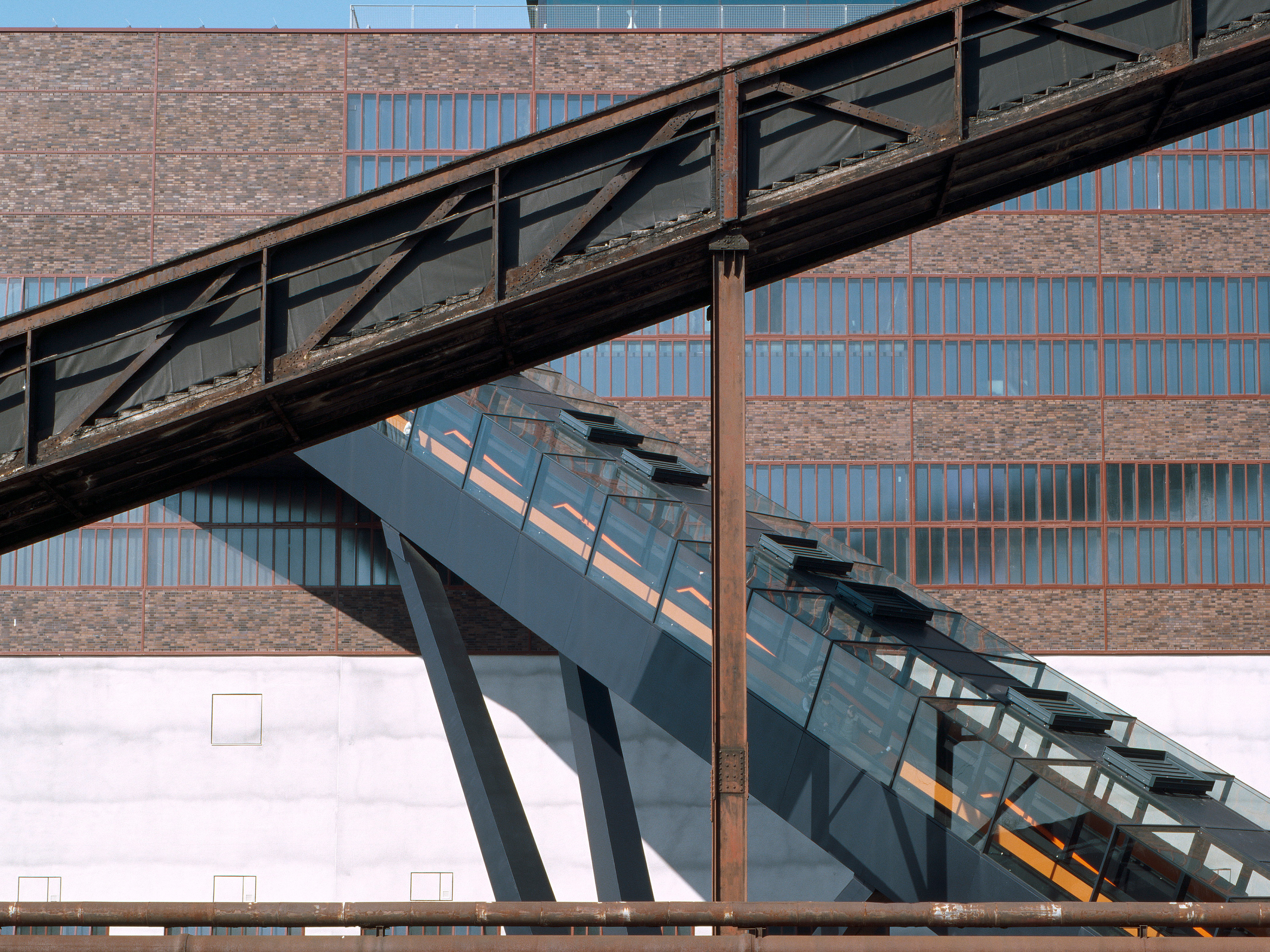

Time, Trace, and Perception Photography as a Form of Knowledge Between Landscape, Abstraction, and the Sublime The photographic practice presented here understands photography not as a medium of representation, but as a process of temporal inscription. The point of departure of these works is not a motif to be depicted, but a real perceptual constellation in which time, movement, and light condense into a visual trace. Landscape does not appear as an object, but as an energetic field within which perception, duration, and materiality mutually permeate one another. Photography is thus conceived not as an instrument of fixation, but as a medium of accumulation. Through long exposure and controlled movement of the apparatus, the image is not produced as an isolated moment, but as a process. The camera does not record a state of the world, but change itself. What becomes visible is not the event, but its temporal extension. In this way, the ontological status of the photographic image shifts: it no longer functions as evidence or document, but as a trace of a perceptual act. This shift has direct consequences for the structure of the image. Objecthood does not disappear entirely, but enters a state of instability. Forms emerge, overlap, and dissolve. Color no longer appears as an attribute of things, but as the result of temporal superimposition. The image is not abstract in the sense of formal reduction, but concrete in the sense of an intensified density of reality. Reality is not negated, but intensified. Art historically, this position can be situated within a lineage that emerges from the dissolution of the classical landscape in modernity. A decisive point of reference is Claude Monet’s late work, particularly the Nymphéas. Here, Monet suspends perspective, horizon, and spatial order in favor of an open perceptual field. Landscape loses its status as a stable site and becomes an experience of light, color, and duration. What is decisive is no longer the object, but the act of seeing itself. The photographic works discussed here continue this development through medium-specific means. While Monet renders time perceptible through painterly means, photography inscribes real duration into the image. Long exposure replaces the instant; movement of the apparatus replaces the gestural hand. The image does not arise from total control, but from a controlled relativization of control. What becomes visible is not the intention of the subject, but perception in the act of unfolding. In this regard, affinities can also be drawn to the work of Cy Twombly. Twombly’s pictorial spaces function as sites of trace, repetition, and temporal inscription. Line and mark refer less to something outside the image than to the act of their own emergence. Meaning arises through presence. This logic is translated into photography: the movement of the camera assumes the function of the gesture, while exposure time replaces the painterly process. The image becomes a space of thought rather than representation. The resulting image spaces evade stable legibility. There is no fixed horizon, no privileged viewpoint, no clear separation between figure and ground. Orientation becomes impossible; instead, the viewer is drawn into a process of tentative seeing. Perception becomes an active, temporal act. The image does not demand narrative interpretation, but experiential engagement. Within the series, this strategy is consistently intensified. While earlier works maintain a certain openness of the perceptual field, movement, contrast, and chromatic layering increasingly condense. In the final image, the reference to landscape is fully transferred into an autonomous pictorial reality. The motif has not vanished, but has been absorbed into a structure of color, movement, and temporal accumulation. Here, the transition from the dissolution of landscape to the constitution of a photographic color field is completed. At this point, the proximity to Abstract Expressionism becomes evident, particularly to the work of Mark Rothko. As in Rothko’s paintings, meaning does not emerge through signs or representation, but through the relationship between color fields. The image operates atmospherically rather than illustratively, confronting the viewer with a state rather than a motif. The crucial difference lies in the medium: while Rothko’s color fields are metaphysically posited, photography remains bound to real processes of light and time. The sublime here does not arise from transcendence, but from the immanent complexity of the world. In a Kantian sense, the sublime manifests as a boundary experience of perception. The imagination reaches its limits without the image dissolving into indeterminacy. This overload is constitutive of the works. It marks the point at which seeing becomes reflexive and transitions into thought. The photographic series is therefore to be understood less as a formal experiment than as a process of knowledge. As the motif increasingly dissolves, the focus shifts from the external world to the conditions of perception itself. The image does not show what is seen, but how seeing occurs. Perception reveals itself as temporally structured, bound to the subject, and yet embedded within a larger relational whole. Photography here functions as a medium of thinking. It does not show what reality is, but how fragile any conception of reality becomes once time is no longer excluded but taken seriously. The images are not representations, but traces—not of things, but of perception itself.